Dimensional modeling

Dimensional modeling is a data modeling technique where you break data up into “facts” and “dimensions” to organize and describe entities within your data warehouse. The result is a staging layer in the data warehouse that cleans and organizes the data into the business end of the warehouse that is more accessible to data consumers.

By breaking your data down into clearly defined and organized entities, your consumers can make sense of what that data is, what it’s used for, and how to join it with new or additional data. Ultimately, using dimensional modeling for your data can help create the appropriate layer of models to expose in an end business intelligence (BI) tool.

There are a few different methodologies for dimensional modeling that have evolved over the years. The big hitters are the Kimball methodology and the Inmon methodology. Ralph Kimball’s work formed much of the foundation for how data teams approached data management and data modeling. Here, we’ll focus on dimensional modeling from Kimball’s perspective—why it exists, where it drives value for teams, and how it’s evolved in recent years.

What are we trying to do here?

Let’s take a step back for a second and ask ourselves: why should you read this glossary page? What are you trying to accomplish with dimensional modeling and data modeling in general? Why have you taken up this rewarding, but challenging career? Why are you here?

This may come as a surprise to you, but we’re not trying to build a top-notch foundation for analytics—we’re actually trying to build a bakery.

Not the answer you expected? Well, let’s open up our minds a bit and explore this analogy.

If you run a bakery (and we’d be interested in seeing the data person + baker venn diagram), you may not realize you’re doing a form of dimensional modeling. What’s the final output from a bakery? It’s that glittering, glass display of delicious-looking cupcakes, cakes, cookies, and everything in between. But a cupcake just didn’t magically appear in the display case! Raw ingredients went through a rigorous process of preparation, mixing, melting, and baking before they got there.

Just as eating raw flour isn’t that appetizing, neither is deriving insights from raw data since it rarely has a nice structure that makes it poised for analytics. There’s some considerable work that’s needed to organize data and make it usable for business users.

This is where dimensional modeling comes into play; it’s a method that can help data folks create meaningful entities (cupcakes and cookies) to live inside their data mart (your glass display) and eventually use for business intelligence purposes (eating said cookies).

So I guess we take it back—you’re not just trying to build a bakery, you’re also trying to build a top-notch foundation for meaningful analytics. Dimensional modeling can be a method to get you part of the way there.

Facts vs. dimensions

The ultimate goal of dimensional modeling is to be able to categorize your data into their fact or dimension models, making them the key components to understand. So what are these components?

Facts

A fact is a collection of information that typically refers to an action, event, or result of a business process. As such, people typically liken facts to verbs. In terms of a real business, some facts may look like account creations, payments, or emails sent.

It’s important to note that fact tables act as a historical record of those actions. You should almost never overwrite that data when it needs updating. Instead, you add new data as additional rows onto that table.

For many businesses, marketing and finance teams need to understand all the touchpoints leading up to a sale or conversion. A fact table for a scenario like this might look like a fct_account_touchpoints table:

| unique_id | touchpoint_id | account_id | touchpoint_name | touchpoint_created_at_utc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23534 | 34 | 325611 | fall_convention_2020 | 2022-01-30 00:11:26 |

| 12312 | 29 | 325611 | demo_1 | 2022-05-29 01:42:07 |

| 66782 | 67 | 325611 | demo_2 | 2022-06-25 04:10:32 |

| 85311 | 15 | 105697 | fall_convention_2020 | 2022-05-29 06:13:45 |

Accounts may have many touch points and this table acts as a true log of events leading up to an account conversion.

This table is great and all for helping understanding what might have led to a conversion or account creation, but what if business users need additional context on these accounts or touchpoints? That’s where dimensions come into play.

Dimensions

A dimension is a collection of data that describe who or what took action or was affected by the action. Dimensions are typically likened to nouns. They add context to the stored events in fact tables. In terms of a business, some dimensions may look like users, accounts, customers, and invoices.

A noun can take multiple actions or be affected by multiple actions. It’s important to call out: a noun doesn’t become a new thing whenever it does something. As such, when updating dimension tables, you should overwrite that data instead of duplicating them, like you would in a fact table.

Following the example from above, a dimension table for this business would look like an dim_accounts table with some descriptors:

| account_id | account_created_at_utc | account_name | account_status | billing_address |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 325611 | 2022-06-29 12:11:43 | Not a Pyramid Scheme | active | 9999 Snake Oil Rd, Los Angeles, CA |

| 234332 | 2019-01-03 07:34:50 | Charlie’s Angels’ Chocolate Factory | inactive | 123 Wonka Way, Indianapolis, IN |

| 105697 | 2020-12-11 11:50:22 | Baggins Thievery | active | The Shire |

In this table, each account only has one row. If an account’s name or status were to be updated, new values would overwrite existing records versus appending new rows.

For fact tables you want to keep track of changes to, folks can leverage dbt snapshots.

Facts and dimensions at play with each other

Cool, you think you’ve got some facts and dimensions that can be used to qualify your business. There’s one big consideration left to think about: how do these facts and dimensions interact with each other?

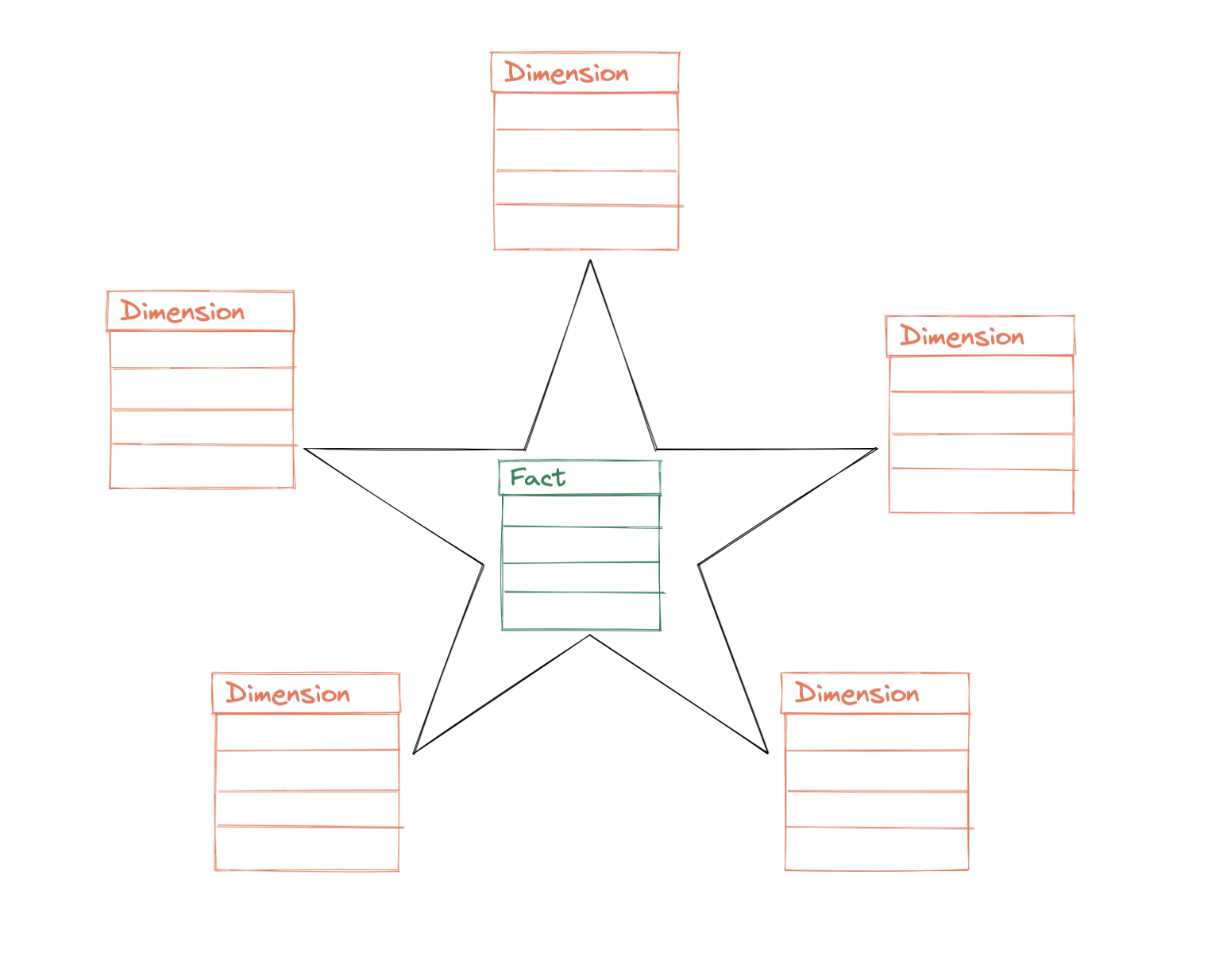

Pre-cloud data warehouses, there were two dominant design options, star schemas and snowflake schemas, that were used to concretely separate out the lines between fact and dimension tables.

- In a star schema, there’s one central fact table that can join to relevant dimension tables.

- A snowflake schema is simply an extension of a star schema; dimension tables link to other dimension tables making it form a snowflake-esque shape.

It sounds really nice to have this clean setup with star or snowflake schemas. Almost as if it’s too good to be true (and it very well could be).

The development of cheap cloud storage, BI tools great at handling joins, the evolution of SQL capabilities, and data analysts with growing skill sets have changed the way data folks use to look at dimensional modeling and star schemas. Wide tables consisting of fact and dimension tables joined together are now a competitive option for data teams.

Below, we’ll dig more into the design process of dimensional modeling, wide tables, and the beautiful ambiguity of it all.

The dimensional modeling design process

According to the Kimball Group, the official(™) four-step design process is (1) selecting a business process to analyze, (2) declaring the grain, (3) Identifying the dimensions, and (4) Identifying the facts. That makes dimensional modeling sound really easy, but in reality, it’s packed full of nuance.

Coming back down to planet Earth, your design process is how you make decisions about:

- Whether something should be a fact or a dimension

- Whether you should keep fact and dimension tables separate or create wide, joined tables

This is something that data philosophers and thinkers could debate long after we’re all gone, but let’s explore some of the major questions to hold you over in the meantime.

Should this entity be a fact or dimension?

Time to put on your consultant hat because that dreaded answer is coming: it depends. This is what makes dimensional modeling a challenge!

Kimball would say that a fact must be numeric. The inconvenient truth is: an entity can be viewed as a fact or a dimension depending on the analysis you are trying to run.

If you ran a clinic, you would probably have a log of appointments by patient. At first, you could think of appointments as facts—they are, after all, events that happen and patients can have multiple appointments—and patients as dimensions. But what if your business team really cared about the appointment data itself—how well it went, when it happened, the duration of the visit. You could, in this scenario, make the case for treating this appointments table as a dimension table. If you cared more about looking at your data at a patient-level, it probably makes sense to keep appointments as facts and patients as dimensions. All this to say is that there’s inherent complexity in dimensional modeling, and it’s up to you to draw those lines and build those models.

So then, how do you know which is which if there aren’t any hard rules!? Life is a gray area, my friend. Get used to it.

A general rule of thumb: go with your gut! If something feels like it should be a fact to meet your stakeholders' needs, then it’s a fact. If it feels like a dimension, it’s a dimension. The world is your oyster. If you find that you made the wrong decision down the road, (it’s usually) no big deal. You can remodel that data. Just remember: you’re not a surgeon. No one will die if you mess up (hopefully). So, just go with what feels right because you’re the expert on your data 👉😎👉

Also, this is why we have data teams. Dimensional modeling and data modeling is usually a collaborative effort; working with folks on your team to understand the data and stakeholder wants will ultimately lead to some rad data marts.

Should I make a wide table or keep them separate?

Yet again, it depends. Don’t roll your eyes. Strap in for a quick history lesson because the answer to this harkens back to the very inception of dimensional modeling.

Back in the day before cloud technology adoption was accessible and prolific, storing data was expensive and joining data was relatively cheap. Dimensional modeling came about as a solution to these issues. Separating collections of data into smaller, individual tables (star schema-esque) made the data cheaper to store and easier to understand. So, individual tables were the thing to do back then.

Things are different today. Cloud storage costs have gotten really inexpensive. Instead, computing is the primary cost driver. Now, keeping all of your tables separate can be expensive because every time you join those tables, you’re spending usage credits.

Should you just add everything to one, wide table? No. One table will never rule them all. Knowing whether something should be its own fact table or get added on to an existing table generally comes down to understanding who will be your primary end consumers.

For end business users who are writing their own SQL, feel comfortable performing joins, or use a tool that joins tables for them, keeping your data as separate fact and dimension tables is pretty on-par. In this setup, these users have the freedom and flexibility to join and explore as they please.

If your end data consumers are less comfortable with SQL and your BI tool doesn’t handle joins well, you should consider joining several fact and dimension tables into wide tables. Another consideration: these wide, heavily joined tables can tend to wind up pretty specialized and specific to business departments. Would these types of wide tables be helpful for you, your data team, and your business users? Well, that’s for you to unpack.

Advantages and disadvantages of dimensional modeling

The benefits and drawbacks of dimensional modeling are pretty straightforward. Generally, the main advantages can be boiled down to:

- More accessibility: Since the output of good dimensional modeling is a data mart, the tables created are easier to understand and more accessible to end consumers.

- More flexibility: Easy to slice, dice, filter, and view your data in whatever way suits your purpose.

- Performance: Fact and dimension models are typically materialized as tables or incremental models. Since these often form the core understanding of a business, they are queried often. Materializing them as tables allows them to be more performant in downstream BI platforms.

The disadvantages include:

- Navigating ambiguity: You need to rely on your understanding of your data and stakeholder wants to model your data in a comprehensible and useful way. What you know about your data and what people really need out of the data are two of the most fundamental and difficult things to understand and balance as a data person.

- Utility limited by your BI tool: Some BI tools don’t handle joins well, which can make queries from separated fact and dimensional tables painful. Other tools have long query times, which can make querying from ultra-wide tables not fun.

Conclusion

Dimensional data modeling is a data modeling technique that allows you to organize your data into distinct entities that can be mixed and matched in many ways. That can give your stakeholders a lot of flexibility. While the exact methodologies have changed—and will continue to, the philosophical principle of having tables that are sources of truth and tables that describe them will continue to be important in the work of analytics engineering practitioners.

Additional Reading

Dimensional modeling is a tough, complex, and opinionated topic in the data world. Below you’ll find some additional resources that may help you identify the data modeling approach that works best for you, your data team, and your end business users: